Guest Article: Prim and Proper

The 2016 Giro d’Italia looms and everyone with a pulse is excited, or should be. The Italian Grand Tour has always been more innovative, ready to shake it up, and we love them for it. And yes, some ideas work out better than others; time bonuses for every stage, including time trials, fuggetaboutit. Wiscot has been doing his usual excellent homework so enjoy and get ready for the Giro.

VLVV, Gianni

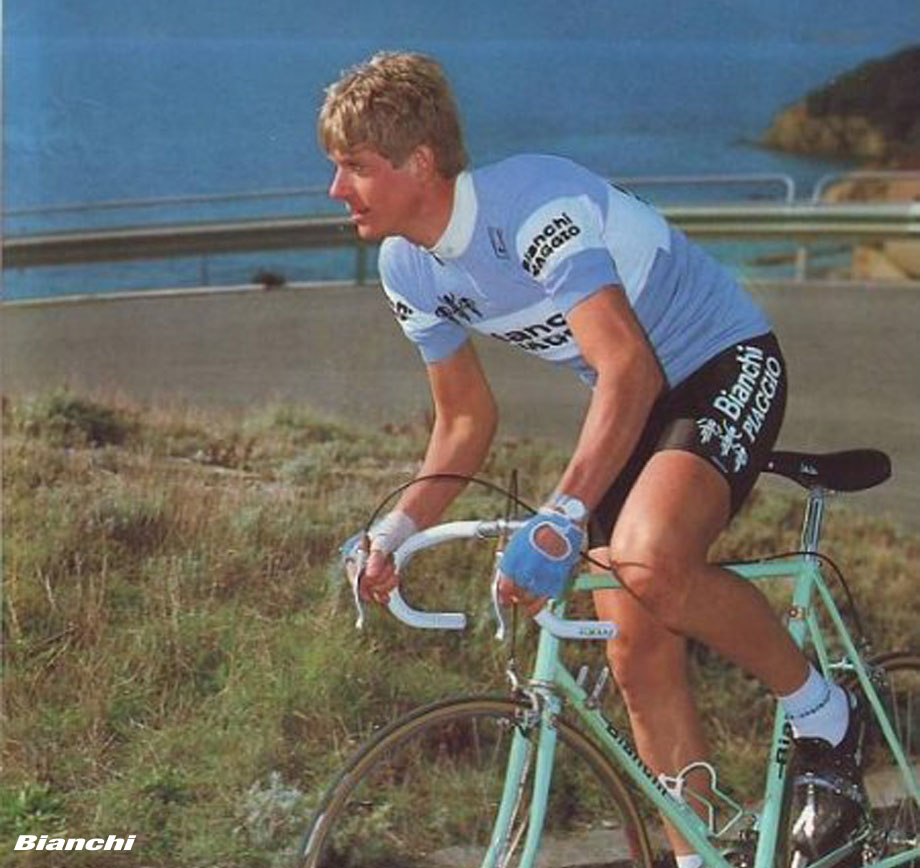

A while ago I penned a profile of Norwegian rider Knut Knudsen who rode for Bianchi between 1974 and 1981. Just as his career was winding down after his oh-so-close-but-no-cigar attempt to win the 1979 Giro d’Italia, he was joined on the team by a massively talented young Swede called Tommy Prim. After outstanding performances in 1978 and 1979 in the highly rated Italian stage race Settimana Bergamasca, at the end of 1979 Prim turned professional with the Italian Bianchi-Piaggio squad. It was not a hard choice: Norwegian rider Knut Knudsen and fellow Swede Alf Segersäll were in the team already. The team manager would be the experienced Giancarlo Ferretti. Good things were on the cards.

Like his Scandinavian teammate Knudsen, Prim would also come agonizingly close to winning a Grand Tour but fall short, not because of physical misfortune, but of the curse of being not from Italy. The situation for Bianchi in 1981 was rather like the philosophical paradox involving Buridan’s ass. This involves said animal being placed between a bale of hay and a bucket of water. The rationale is that the ass will chose whichever is closer. The result, however, is that the ass can’t decide which to go to – the water or the hay – and subsequently dies of hunger. Such was the scenario for Bianchi in 1981. On the team were the Swede Prim and Italians Silvano Contini and Gibi Baronchelli. Neither Prim, Contini or Baronchelli can be considered asses, in fact they metaphorically represented hay and water. The ass was Ferretti who couldn’t decide on which rider to go with as leader and so squandered his chances to win. Another ass was race director Vincenzo Torriani who, in a move designed to slant the race Giuseppe Saronni’s way, introduced of a series of time bonuses for each stage. First place earned a 30 seconds bonus, 20 seconds for 2nd and 10 seconds for third. Even the three time trials carried bonus seconds! This would dramatically affect the result more than he could have anticipated.

In addition to the expected Moser-Saronni rivalry, other Italians ready to go for pink were Roberto Visentini of Sammontana-Benotto, as well as the Bianchi trio of Prim, Contini and Baronchelli. Also at the start line was Inoxpran’s Giovanni Battaglin. No-one rated his chances as he had just won the Vuelta d’Espana and back in those days these two Grand Tours basically butted up against each other. Battaglin started the Giro on three days rest. What was not reckoned with was Battaglin’s smarts and realization that it was very much a case of playing the long game and seeking consistently good stage placings ― and taking advantage of rivalries. For example, by stage 6, Saronni had three wins and 90 seconds of bonuses that gave him the maglia rosa by 24 seconds from Moser.

By stage 18, with just three stages to go, the opportunity to win overall looked good for Bianchi with three riders in the top five. A clean sweep of the podium was not beyond hope. Contini held pink, followed by Prim at 59 seconds, Battaglin at 1:35, Saronni at 1:42 and Baronchelli at 1:59. It was that close. However, stage 19 saw Battaglin make his decisive move on a 208 kilometer mountain ride to San Vigilio di Marebbe that tackled the Palade and Furcia climbs. The Inoxpran rider won the stage by 10 seconds from Saronni with Prim tied for third with Josef Fuchs 11 seconds behind the winner. The bonus gave Battaglin an additional 30 seconds on top of the time gaps with Baronchelli and Contini both losing 1:02 on the day. Contini now led Battaglin by only 3 seconds with Prim a further 5 seconds back. Just as the Vuelta winner should have been on his knees after almost six weeks of racing, he was getting stronger and Ferretti was looking more and more like Buridan’s ass.

Battaglin then turned the screws tighter on the mountainous stage 20 to Tre Cime di Lavaredo, knowing that with a sprint stage and a short time trial to come, he needed to gain as much time as he could when he could. He finished third behind ace climber Beat Breu and veteran Josef Fuchs, gaining another ten bonus seconds to put him in pink, Prim and Contini finished 35 seconds and 1:37 behind respectively. The sprint stage was won by Pierino Gavazzi and didn’t affect the general classification. Prim rode his heart out to finish second behind teammate Knudsen in the final time trial but the Inoxpran rider finished third for ten more bonus seconds giving him a total of 60 seconds in bonuses for the whole race. Contini and Baronchelli were well outside the top 10 on the last day.

When Battaglin pulled on the final maglia rosa in Verona, he was the winner by 38 seconds from Prim. On actual time, Prim had won, but Battaglin had won more bonuses because of one stage win and three 3rd places. Prim had one 2nd place. Saronni was third at 50 seconds – a result more than aided by the 2:10 in bonuses he accumulated. Calculating time bonuses overall Battaglin had picked up 60 seconds, fifty of those in three of the last four stages; Prim had accrued 20. Bonus difference? 40 seconds to the Italian. The rules had been established on stage one and Inoxpran played them to maximum advantage.

The feeling that Prim coulda, woulda, shoulda won is hard to shake. His second place was no flash-in-the pan. It did show however, a lack of tactical nous by Ferretti who should have played his cards better. Designating a single team leader and watching who got top three placings would have helped the Bianchi cause. Instead, Battaglin and his DS Davide Boifava played the field like a fiddle – aided of course, by Battaglin’s remarkable form and tactical smarts in timing his efforts to perfection.

In 1982 Prim finished second in the Giro again, this time beaten by the majestic Bernard Hinault by 2:35. Again, Bianchi went with two captains and Prim and Contini finished 2nd and 3rd twelve seconds apart. In 1983 he was the designated leader for Bianchi and took the maglia rosa after the first stage team time trial. Alas it did not last and poor form in the mountains saw him finish 15th. In 1984 Prim was on form, winning Tirreno–Adriatico stage race but he crashed right before the Giro. 1985 saw Moreno Argentin brought onto the Sammontana-Bianchi squad and the Swede finished fourth behind such greats as Bernard Hinault, Francesco Moser and Greg LeMond. 1986 was the beginning of the end as his 21st place in the Giro saw his team withdraw from the Tour of Sweden which they – and he – had always ridden since its reintroduction in 1982. So disgusted by this, Prim announced his retirement. He was 31.

After his retirement, Prim held various jobs: he opened a bike shop in Sweden, worked for a mail order firm, a saw mill and then a salmon smokery. From 2000 – 2004 he was team manager at Team Crescent, a Swedish pro squad designed to develop Swedish under 23 riders, but he will be remembered as a rider who was not just good but great but also unlucky. It pays dividends to not just play by the rules but truly understand them and it’s not always the strongest who wins, but the smartest.

I am blessed to be getting to go the Giro for the first time. My wife and I will be there for 10 days. I am so exited I can hardly wait. And yes, I am taking a bike across the atlantic and going to ride the hallowed roads.

Strong work, @wiscot I always liked Prim so it’s good to read about him, thanks!

More eighties gold I just found here:

http://player.bfi.org.uk/film/watch-six-days-in-romandie-1983/

I remember seeing this when I just started going out with a cycling club and it was probably responsible for me being still mad for it 33 years later. VLVV

Great story, thanks Wiscot.

Normal

0

21

false

false

false

SV

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Normal tabell”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0cm;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:”Times New Roman”,”serif”;}

As a junior rider in Sweden I was in a break with Prim once. I was advancing on the outside of the bunch and when I was just behind Prim he attacked and I, who seldom managed to even follow the bunch all the way to the finish, instictively (it was not a descision, belive me) managed to hang on to his wheel. After a couple of hundred metres he swung out a little to the left, it was my turn to work. Wich I already did. And I just wasn’t able to get up there, we were way past my normal racing speed. So he swung back and continued to pull for another hundred metres and steered to the side again. And this time he turned his head and stared. I was ashamed and desperate. I just had to get upp and pull so I raised myself from the saddle and put on the highest sprinting speed I could manage. OK there were 75 kms left to race but never mind now it was all about just getting upp there. Yes, I succeded to get in front and at the same moment as i sat down to establish a tempo, swoosh, came the whole peloton. That was it.

@wiscot Nice article, enjoyed it. I’m not well versed in Giro lore, thanks for the history lesson.

@Tomas Nilsson

Thanks for sharing that story!

Cracking read thanks @wiscot . Just finished an excellent article on Roberto Vissentini in Pro Cycling that you would enjoy. It was clearly a disadvantage at the Giro (some say a disadvantage in general ) to not be born Italian.

@gilly

Thanks! Yeah, I can’t imagine that if Roche finds himself in Italy, he doesn’t spend some time with his old buddy Roberto. That was a crazy Giro and the Giro sets a high bar for craziness!