Guest Article: Le Metier

The Velominati are proud to present the following guest article by our community member Steampunk, who splits his time between peppering the site with his insight and humor and riding in the sacred Velominati colors.

Michael Barry is one of the great domestiques of the peloton; loyal, hardworking, a hardman, a true cycling aesthete – and an excellent writer. What follows is more than a book review; it is an account of Steampunk’s acquisition of the book, a fine description of the contents, and account of some of the discoveries and revelations it provided to this particular Velominatus.

Thanks, Steampunk, it would appear I need to go order yet another book from Rouleur.

Yours in cycling,

Frank

—

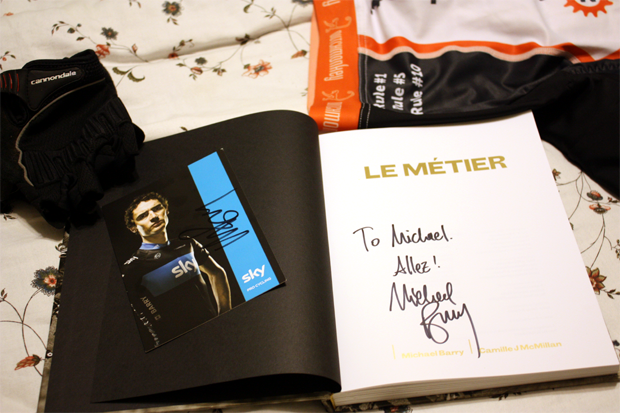

I have a new prized possession. A couple of weeks ago, Michael Barry paid a visit to my local coffeeshop. Because I don’t abide by Rule #11 (more on that another day), I was forced to miss the book signing and short ride, but I was able to arrange for a signed copy of Barry’s new book, Le Métier, to be held for me. Later that week, I picked it up, and spent that and the following evening poring through it. It’s taken me some time to absorb the book and situate it within my reading of cycling””both in my standing as a fan of the sport and as an avid cyclist. It’s a beautifully-produced, hardcover book from Rouleur, rich with numerous stunning photographs by Camille McMillan, most of them from 2008.

Barry’s words aren’t outdone by the lavish photography. Visit his blog, and you realize very quickly that he is a quietly thoughtful and articulate guy. This carries through in the book, which is a contemplative and moving account of the daily work of a professional domestique. The book is divided into four chapters: “Winter,” “Spring,” “Summer,” and “Autumn,” as though to present a year in the life. But rather than present a blow-by-blow tell-all of his adventures on the Pro Tour, Barry pulls back a little further, bouncing his narrative around a bit to provide not an autobiography but instead a melancholy documentary that is less about himself and more about””as the title indicates””le métier.

Le métier can translate loosely into English as “the job,” but a better translation probably revolves around something like “the trade” or “the craft,” stressing both technique and experience. In Barry’s hands le métier is also something just this side of an addiction. He describes in such vivid and painful prose the struggle and agony inherent in professional cycling””the crashes, the hospital rooms, the suffering, the travel, the stress, the exhaustion””that I found myself recoiling in guilt from my eager anticipation for the Spring Classics or the Grand Tours. By and large, Barry portrays a miserable existence, saved only by the fact that these select few are permitted””blessed””to make a living doing something they love, even if le métier is a far cry from aesthetic and beauty of cycling that drew them to the sport in the first place. This is the addiction. The tone and pace of the book are most peaceful when Barry describes his pre-season training rides around his home in Girona, Spain. In those excerpts, before the frantic training and racing that will follow, he seems at peace and the rhythm of the bicycle provides freedom. It is, of course, the same machine and the same activity that enslaves him the rest of the year, keeping him from family and milking every last ounce of power and energy from his body and soul.

He concludes the final chapter with the following:

Each cyclist fights an internal battle. Some fight on the bike because it gives them purpose and simplifies the complexities in life. Others escape. Others ride to fill a void. Others battle childhood disturbances. Others pedal for fitness or weight loss. We each have our reasons.

…

Over the hundreds of thousands of kilometers I’ve ridden, I’ve slowly come to realize why my desire developed and became an obsession. Without it, I struggle””I am anxious, unfocused, and tense. Cycling has become spiritual, as it is a passion that I can pursue in the natural environment. I can pedal away angst, find calm and clarity with the rhythmic motion and freedom. The commitment gives me focus; the love gives me panache. Whether it is pedaling to victory or training in the mountains, I find peace.

Michael Barry is basically Jens Voigt, but without the countless sound bytes and cult following. He is quiet and controlled. But he knows his job and he does it as well as anyone on the Pro Tour. He is the quintessential professional: grounded, committed, talented, and loyal (he offers genuine and persuasive portraits outlining the better qualities of former teammates Lance Armstrong and Mark Cavendish). He is also as smooth and natural a rider as you’ll likely find in the peloton. He was born to ride. But his personal victories are the team victories. His success is rarely tracked or noticed by cycling enthusiasts, but the massive pull at the front for long kilometres on end to catch a breakaway or to help set up his team’s train or to protect his team leader: this is honorable stuff.

And as the weather here””not far from Barry’s hometown of Toronto””takes a turn from hot summer to cooler and wetter autumn, echoes of Le Métier are evoked in my own riding. At all levels, good riding involves suffering. Out on a lonely spin early this morning in the crisp air, I can’t put myself at the head of the peloton pulling for my team leader, but I can appreciate the freedom of the ride, not dissimilar from the moments Barry clearly cherishes. I can feel the cold air straining my lungs as I climb out of the saddle, and I can begin to appreciate the hook that continually brings Barry back to le métier, no matter the tribulations that the season will hold. For me, though, this is no professional obligation; it is a recreational activity. As I settle into a comfortable rhythm along a flat stretch of road, trying to hammer out a steady and high cadence, I take pleasure in the incremental improvements in form and fitness that have accompanied every ride this summer and fall. These gains are ridiculously modest, but they contribute to molding an ever-evolving relationship between rider and bicycle. Le Métier is about that conversation between body and machine. There is an artful beauty in this, too often lost in a day at the office.

Some discoveries and revelations:

- I can no longer begin to believe that I can even come close to achieving any modicum of Rule #5.

- In the many photographs of Barry training on his own, with David Millar, George Hincapie, and others, I was amazed to see how many rules were blatantly broken; and bikes and riders still looked great. Of course, by the time you are riding at the professional level, you have transcended any and all rules. More to the point, you’re providing the inspiration for new rules.

- There were no bling wheels on any of the training bikes photographed. Good, fast, reliable, sturdy: yes. But nothing that screamed out for attention.

- Bikes, too. Many seemed cobbled together with bits and pieces that had been left over in the shop. Put another way, though, the style to which the Velominati aspire is very clearly an aspect of professional racing (dominated by sponsors who insist that their product looks good) than as part of the culture of riders themselves, many of whom just want to ride.

- The quiet, undiscussed camaraderie among riders, but obvious in the photographs is interesting. Barry and Millar seem to spend a lot of the off-season training together, even if they then go to war against each other for their respective teams when the season is underway.

- Girona looks like a very cool place to live and ride, especially if so many professional riders are in the neighborhood.