Guest Article: BC – Before Cancellara

@wiscot is at it again. He is the Velominati historian and I’m always pleased when more of his writing arrives at the bunker. Luckily for all of us, cycling has a long history, most of which we are unaware of. This was not taught at school. Any article that includes the words Spartacus and Hour Record in the first paragraph already has my attention. Read on.

Yours in Cycling, Gianni

When Fabian Cancellara inevitably retires, his palmares will be astounding: the grand tour stage wins, the leader’s jerseys, the multiple wins in the monuments, but above all, he will be remembered and revered for his powerful time trialing abilities. On his day, the big Swiss turbo could fly over a course faster than anyone with ample style and class to spare. Indeed, when it comes to panache and power, few equal Spartacus. If rumor is to be believed, he is going to attempt the Hour Record before he retires and only a fool would bet against him.

However, as in all things cycling, there are precedents and precursors. For Fabian, I’d like to put up one Daniel Gisiger as Exhibit A. Born in Baccarat in 1954, this Swiss rider had a highly respectable career with 44 listed wins. If it comes to pass that Cancellara begins the last few years of his career with an hour record attempt, Gisiger began his in June 1977 when he set a new amateur record of 46kms 745m. Bear in mind that this was only 1686 meters less than Merckx’s 1972 record that was done at the height of his career and at altitude. Gisiger did his at the Hallenstadion in Switzerland – high, but not as high as Mexico. And, as we know, Cancellara will have to use a bike very similar to that used by Merckx and Gisiger and will likely go to altitude.

Over his career Gisiger excelled at the race of truth just as the art of competing against the clock was becoming a highly specialized aspect of the sport. No more the jersey tucked into the shorts and a pair of light wheels on the regular road bike for the TT. By the early 1980s skinsuits were becoming de rigeur and manufacturers were coming out with more and more special aero gear to cater to the TT boys. (By the mid-to-late 1980s the “funny bike” craze was red hot but the UCI finally ensured that that kind of out-of-the-box thinking and development had its lid firmly shut).

In the early 1980s pedigreed time trials such as the Grand Prix des Nations and Baracchi Trophy were still mainstays of the calendar and the big names took them seriously. A quick review of the past winners of both reads like a “who’s who” of the sport. These races were not some Tour of Beijing/Japan Cup-type end-of-season filler for those looking for an autumnal jaunt to save a season or a contract, but hard fought races that carried huge prestige.

Indeed, before there was an official World Time Trial Championship race the Nations was the de facto world TT championship. When Gisiger rode it it was held over two laps of a brutal circuit in Cannes. How tough? In 1988 I watched the race from the roadside and to be fair, it should have been classified a hilly TT. This was no settle-into-your-rhythm race, it required massive concentration, quick reflexes and great bike handling skills as it snaked and twisted around the city. Gisiger excelled in both races winning the Nations in 1981 and 1983. In 1982 he was second to Bernard Hinault by a scant 2 seconds; third place finisher was Bert Oosterbosch at a whopping 2:29 back. And when he won in 1983 he beat Lemond by 1:47 and Oosterbosch (again) by 2:53. The Swiss tester also won the Baracchi in 1981 (with Serge Demierre), 1982 (with Italian ace Roberto Visentini) and 1983 (with Silvano Contini).

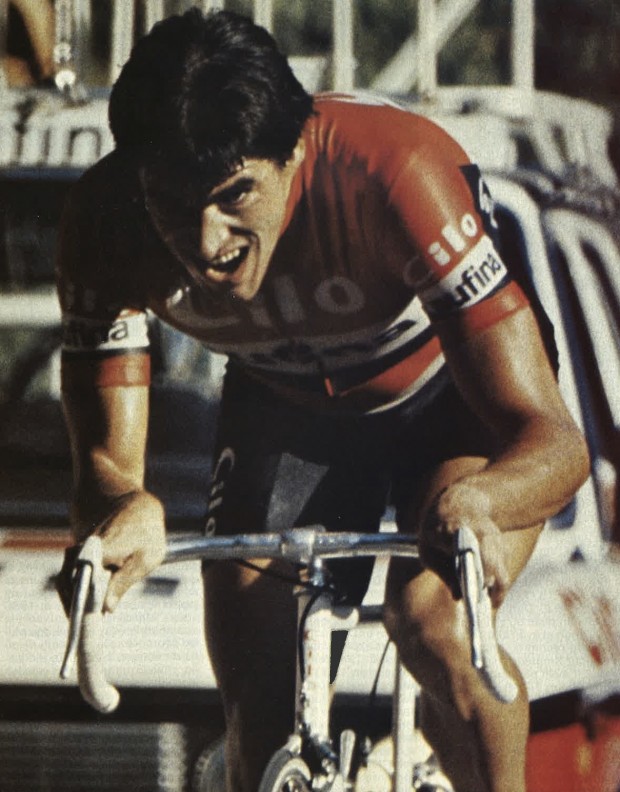

So, let’s look closer at the evidence that Gisiger was a top tester. His wins are written in the record books, but the images complete the story. The physique: muscular, lean and powerful; the position: sweet flat back; the bike stripped to the bare minimum with half-taped handlebars which are drilled to allow the brake cables to be hidden and keep the cockpit clean. The early aero brakes. No helmet, no shoe covers, no disc wheels. There’s something beautifully elegant and minimalist about this which is marvelously appropriate: it is purely man against course and clock. The helmets, sunglasses and aero bikes of today give the riders a somewhat otherworldly appearance that I feel engenders a disconnect between spectator and rider. It’s like watching Formula One: you see the car and driver but not the full human effort required.

If his TT abilities weren’t enough, Gisiger rode””and won””in all other aspects of the sport. In addition to the TT wins cited above there were 4 Swiss National track championships, 6 Six Day races (including the Zurich six day race with fellow Swiss powerhouse Urs Freuler when both rode for Atala), 11 criteriums, 5 road races and 5 road stages. And, to top it all, that 1977 Amateur World Hour Record. As if this was not enough, Gisiger rode his prime years in the Malvor-Bottechia, Cilo-Aufina and Atala team colors making him one of the lucky riders who spent most of his career in classic team kit.

Daniel Gisiger’s career will never match that of Cancellara. There are no monument trophies or yellow jerseys in his closet. What we do have is a rider who was a versatile champion of the sport. He rode in an age of transition, between the tried and true ways of cycling that had changed little from the 50s and 60s, into an age of great technological development and a more scientific approach to performance. To wit: his trainer was Paul Kochli, the Swiss guru who would go on to work with the likes of Bernard Hinault, Steve Bauer, Andy Hampsten and Greg Lemond at La Vie Claire, honing the physical potential of his charges with a more scientific approach to diet and training. Known to be a staunch anti-doping advocate, Kochli left the sport in the early 1990s as the drug scene became too rampant to ignore. Gisiger was an early beneficiary of his tutelage and made a bold mark upon the sport. His name is rarely head these days but should be remembered more fondly: all sports have their eras and associated champions, but there are always transitional figures who get swept aside by the narrative of history. Daniel Gisiger was one such rider: a fearsome competitor against the clock be it on the boards or the road. If and when Cancellara goes for the hour, I hope Gisiger is watching his countryman with the satisfaction of knowing that he helped pave the way.