Guest Article: Putting the V in Rivat

I’ve been waiting for the other shoe to drop in the Lance affair. That is a long wait. And I’m burned out on the whole doping subject so it’s great @wiscot writes up a profile of Charlie Mottet. Here is a man whose sock height I can believe in.

VLVV, Gianni

It was, in the first instance, the shoes. Just as cycling kicks were emerging, literally, from the dark ages in the late 80s, French rider Charly Mottet wore perhaps the finest shoes of his generation: red and white Rivats. Not too garish, not too bulky, not too cheesy-looking, they were just right and, to a great extent, complemented the rider who wore them: a professional who did things properly. They got my attention and he became a favorite rider for me. As we now know, Mottet did indeed do things “just right.”

In his recent memoir “We Were Young and Carefree” Laurent Fignon writes bluntly and tellingly that in the early 90s there was a subtle, but seismic shift happening in pro cycling. Riders, previously considered domestiques, were riding beyond their expected abilities. Champions with exemplary palmares, like Fignon, found themselves struggling against riders who were previously fit only to fetch bidons. While it must be said that doping has always been present in cycling, it was relatively unsophisticated and tended not to turn “carthorses into thoroughbreds.” The 1990s however, saw much more sophisticated and powerful drugs becoming the norm and while EPO might not have been openly discussed or detectable, clearly something was amiss. Fignon writes of his disgust and despondency at being humiliated in the sport he loved – hence his decision to retire rather than follow the same unsavory path to dishonesty.

One rider whose own palmares were outstanding and had a reputation for attaining them honestly was Fignon’s one-time teammate Charly Mottet, The diminutive rider from Valence in the Drome region began his career with Renault in 1983, a top echelon team that included Fignon, Marc Madiot and Bernard Hinault. Under the guidance of brilliant directeur-sportif Cyrille Guimard, Mottet, like so many others, flourished in his profession. He then rode for Systeme U (again under Guimard) and RMO before retiring after two seasons with Novomail. In retrospect, his 1994 retirement (one year after Fignon) was timely and dignified. In the mid-90s and beyond, doping was becoming de rigeur and riders like Mottet would have encountered the same dilemma most riders would face: dope or be dropped. David Millar (to name but one) succumbed; Mottet did not.

Even a cursory glance through Mottet’s palmares show a rider of versatility and strength: 45 victories in the amateur ranks and 75 wins as a professional. In his second pro season he was best young rider in the Giro and winner of the Tour de l’Avenir. He won stages in all three Grand Tours, the Tour of Romandie overall and the Dauphine Libere three times. In one day classics he won the Tour of Lombardy and Zuri-Metzgete. Digging deeper, we see a rider of amazing all-around abilities: he could time trial, winning the Grand Prix des Nations three times; he could climb, winning Romandie, the Tour de Haut Var and the Dauphine; and he rode track, winning the six days of Grenoble (twice), and Paris. He won 6 top-level criteriums. In his grand tours he finished 2nd in the 1990 Giro and was three times in the top 10 in the Tour.

But what really sets Mottet apart from many of his fellow pros as the age of rampant drug-taking dawned was that he was known to be a clean rider. No ifs and buts or suspicions, he was clean. Disgraced soigneur Willy Voet, who would be at the center of the doping maelstrom with Festina, worked with Mottet and remembers him well: “A year later the French rider Charly Mottet, who twice finished fourth in the Tour de France, joined the team. The arrival of Charly Mottet helped to clean up the team. He was the team leader, he had more influence than anyone on the way his teammates thought and he never wanted to know about drugs. When he arrived at RMO, we knew hardly anything about him. We knew he had the ability to win the Tour de France, but we didn’t know what means we had to put at his disposal to help him get there. It was only as the races went by and we ate with him and spent time with him that we worked out what kind of a fellow we were dealing with. This was one clean cyclist. An iron supplement or an injection of an anti-oxidant (Iposotal) and that was as far as he went.”

“You could honestly say that Mottet was a victim of drug-taking right through his career – of other riders’ drug-taking. If he had used some stuff to help him recover, perhaps only now and then, the list of races which he won – already a long one – would have been considerably longer. Who knows if he might not have won the Tour? As it was, he was a rider who was said to fall apart in the final week.”

Maybe Mottet also became disillusioned as lesser talents usurped him? After all he retired at the age of 32 when he could have been expected to ride for a few more years. Nevertheless he has a record to be proud of and something that no amount of money or rationalizing can give: a clean conscience. The pressure to stay active and dope must have been immense: by the early 90s, the French had enjoyed many years of Tour triumphs. Beginning with Jacques Anquetil (61, 62, 63, 64) followed by Lucien Aimar (66), Roger Pingeon (67), Bernard Thevenet (75 & 77), Bernard Hinault (78, 79, 81, 82 & 85) and Laurent Fignon (83 & 84), the French had 15 wins in 25 years – a remarkable run of success. With Hinault retiring in 86 and Fignon struggling in the LeMond years, the expectation and hope for a new great French hope was palpable. Why would such dominance not continue? Mottet looked a possible successor to the fame and fortune that a Tour win would bring. Alas, the dark and pernicious encroachment of doping meant that Mottet began to struggle against other riders who were theoretically not in his league. It’s hard to believe that the diminutive Frenchman would not be aware of talk and rumors as well as unexpected results. To maintain a drug-free stance in the face of on-and-off the bike pressure shows a remarkable strength of character. Recent books by David Millar and Tyler Hamilton as well as the recent USADA report bear stark witness to the Hobson’s choice riders faced: dope or be dropped. Tellingly, the only Frenchman to podium since 1990 has been Richard Virenque and, through Voet and other sources, we all know about his stance on performance-enhancing drugs.

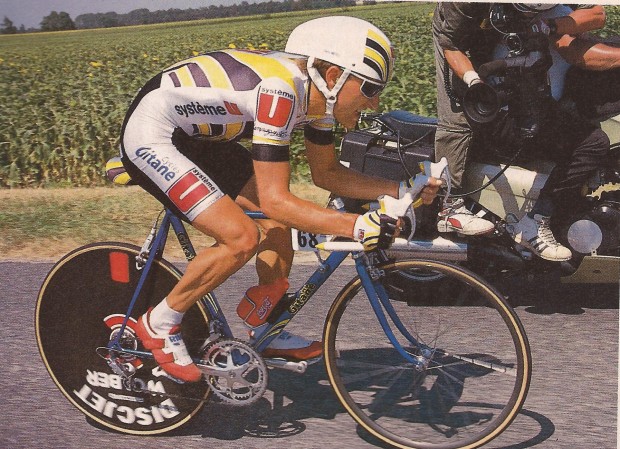

Here at Velominati we look backwards to bygone days to seek warmer memories than seem plausible today. Riders come and go but some remain in the memory as examples to be honored and Charly Mottet is one such rider. Look at the picture above for reasons why Charly was the consummate professional:

- The full effort being expended: the essence of V.

- The superb position with the flat back.

- The radical (by standards of the day) Gitane TT bike with full Campagnolo Delta gruppo.

- The immaculate and stylish Systeme U skinsuit with matching custom saddle.

- The aero helmet paired with cool Rudy Project sunglasses.

- The red aero Coke bidon.

- The perfect socks.

- The magnificently color-coordinated outfit; look how the red shoes sync with the U logos, the bidon and the decals on the rear disc wheel. A more put together rider you will struggle to find anywhere.

- And last but not least, the red and white Rivat shoes.

What’s not to like and admire? Nothing. Hopefully our sport is going through a catharsis where the misdeeds of the past will be banished to awkwardly-written record books. Sure, some riders will always look for an edge, but I believe the new generation are riding cleaner than they have in decades. On this site we can, and do, express our opinions readily and with conviction. However, none of us were pro riders in the 90s and 2000s and can’t really say what we would have done if put in the same position most riders found themselves in. They say that to truly understand someone, you have to imagine standing in their shoes; in more ways than one, I’d like to think that we, as Velominati, could stand in Charly’s Rivats.