Guest Article: Bernard Hinault’s 1980 Liege-Bastogne-Liege

Unfortunately the weather for 2013 L-B-L looks a lot nicer than the 1980 episode. Then again, if the weather looked that bad, they might have cancelled the race or put them on buses before Bastogne and driven them back towards Liege. Who would be the Badger of the peloton of this year’s race in those conditions? Discuss. As always, we have @wiscot to thank for another great historical guest article.

Yours in Cycling, Gianni

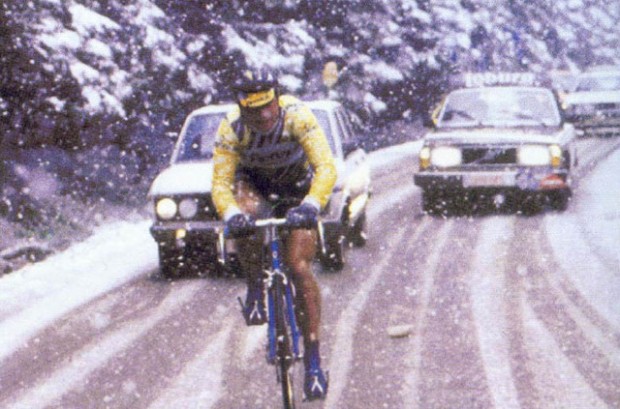

Bernard Hinault’s tires swished and hissed as they plowed through the snow and slush. They were chorused by his rhythmic heavy breathing, the dull roar of the attendant cars and motorbikes that hovered behind him like a hallelujah choir (or a bunch of vultures), and the occasional cry of support from a hardy fan beside the wintry road. Whatever the outcome of the Frenchman’s audacious solo attempt to win Liege-Bastogne-Liege, his team car and the media wanted to be there to celebrate his win “’ or feast on his failure.

Snow had been ever-present since the first of Liege-Bastogne-Liege’s 244 kilometers and, according to L’Equipe, Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle said that some riders picked up their race numbers and didn’t start – they returned to their hotel. As the race wore on the weather got worse inflicting massive attrition upon the peloton: by kilometer 70, 110 of 174 starters had abandoned. Hinault, who despised bad weather, had, in fact planned on retiring at the Vielsalm feeding station but instead, changed bikes and continued on, partially because his teammate Maurice Le Guilloux was still in the race and as team captain, his pride meant he wanted to be the last to abandon. Hinault also persevered because he had a strong bond with L-B-L: in 1977 as a new pro, Hinault won the race, and in 1979 he finished second.

At the top of the Stockau, Belgian hardman Rudy Pevenage led by 2:15. Twenty kilometres later Hinault and his companions Ludo Peeters, Silvano Contini and Henk Lubberding pulled him back. With 80 kilometers to go, Hinault attacked on the Haute-Levee. Perhaps too cold to respond or hopeful that he couldn’t ride 80 kms to the finish by himself, no-one else joined him. This raised two intriguing questions: would Hinault tire and succumb to the literally bone-chilling cold or would he register one of the most audacious classic wins in living memory? Undeterred and displaying the unmatched mental and physical fortitude that were rapidly becoming his trademark, the Renault rider built a lead of a minute, then two, then three. “I didn’t look at anything. I saw nothing. I thought only of myself” he later said. By the end of the race he would arrive in Liege not just alone, but an astonishing 9:24 ahead of second place finisher Hennie Kuiper. So emphatic was this winning margin that Kuiper recalled “When I finished, there was almost nobody on the line. Radio and television media were already gone.” By the time the 21st and last finisher, Jos Wilstein, crossed the line he was almost 25 minutes behind Hinault. It was one of the most impressive and emphatic victories in a monument ever.

How bad was it? Even though he finished 11th, Duclos-Lassalle told L’Equipe in 2010 that he didn’t even remember finishing. Apparently, many of the abandoned (and never started) riders who did remember were warmly ensconced at the Ramada hotel 200 meters from the finish line. Hinault, knowing where they were, saluted them from his bike “like a general reviewing his troops” according to reports. If there can ever be any doubt as to why Hinault became “le patron” of the peloton, it was victories such as this that brutally reminded his rivals that he was in a different class from them when he put his mind – and legs – to the task at hand.

Heading to the podium to accept his laurels, Hinault was relieved and happy that he had won such a prestigious race. He was also in some dry clothing. However, upon returning to the team hotel, the story is told that he had to be given a tepid bath, because a hot one was too much for his chilled body to bear. Yet one thing bothered him as his body thawed – he couldn’t feel the tips of several of his fingers. The first reaction was that this was just a temporary loss brought on by the hours spent in the cold and wet. Unfortunately, this was not the case. As the weeks, months and years rolled by the numbness remained, and permanent loss of feeling in one or two fingers (accounts vary) were his lasting souvenir of one of the most epic classic rides in cycling history. Even today, temperatures in the 30s mean he dons gloves because his fingers are still so sensitive to the cold.

Hinault’s victorious ride was that of a champion in more ways than one. Even though he was only beginning his fourth season as a professional, he had already won Liege-Bastogne-Liege (in 1977, also in poor conditions), Ghent-Wevelgem, two GP des Nations, two Tours de France, two Dauphine-Libere and one Vuelta. Later in 1980 he would win the world championship road race at Sallanches on one of the most arduous courses ever used. Less than halfway into his career his palmares already put him among the all-time elite of cycling. Yet what truly puts Hinault’s 1980 Liege-Bastogne-Liege win beyond the normal expectations of such a great rider is that Hinault was never keen on the cold and wet: no-one would have blamed him for climbing off. But he didn’t. He stayed on and won.

Likewise, Hinault hated Paris-Roubaix, claiming it to be a lottery of a race where the most deserving victor didn’t always win because of bad luck and circumstances beyond their control. His opinion on this matter never wavered and he could have treated the race with the contempt he felt for it. Instead, in 1981, he won, beating such Paris-Roubaix specialists as Moser, De Vlaeminck, Kuiper and DeMayer in a six-man sprint in the Roubaix velodrome. This was despite two crashes and several punctures that would have seen lesser riders give up before reaching the finish.

Hinault retired in November 1986 at the age of 32 when other riders would have gone on for a few more highly-paid years, showing occasional glimpses of past greatness, but getting upstaged regularly by younger riders. Not for Hinault; his past achievements, his pride, his ability and his mental fortitude meant he showed no fear to the competition, the weather or the parcours. This is what truly elevates champions above even great riders: when they have every reason to quit they conquer their opposition be it competitor, weather, terrain or their own psychology in the most emphatic and decisive manner.

This is why we, as Velominati, love and cherish the Monuments. Each edition of the famous five has the distinct possibility of creating another legend in our sport. Today’s professionals ride alongside the ghosts of the past; their wins are put into context. Regular riders such as us can ride on the same roads and get a personal appreciation of what the professionals do. Few sports offer such opportunities to relate on the most physical and emotional levels. Liege-Bastogne-Liege, first run in 1892 – 120 years ago! – raises more ghosts than the rest and whatever exploits the riders perform this year, the still-living spectre of Bernard Hinault will haunt them all.