In Memoriam: Il Pirata, Broken-Hearted Saviour

There’s an air of Shakespearean tragedy to the death of Marco Pantani on Saint Valentine’s Day in 2004. Once the most famous cyclist in the world, he died alone in a hotel room on a day devoted to love.

But his love – Cycling – had betrayed him. Once a fixture of the Nineties European road racing scene, he was part and parcel of the culture and spirit that embodied that era. Sensationally, as he was about to win the Giro d’Italia for the second time in 1999, he was thrown from the race after a failed hematocrit test on the morning of the penultimate stage. At a time when doping was rampant throughout the peloton and, as we are beginning to understand now, secretly supported by both the teams and governing bodies, Pantani was torn from the world he knew like a puppy from a warm house and abandoned in the winter cold. He was singled out, vilified, made example of. Confused and betrayed, he would never recover.

A rider defined by brilliant highs and devastating lows, he fit the mold of “enigmatic climber” so well it almost feels cliché to point it out. He won atop nearly all the most famous climbs in cycling and still holds the record for the fastest ride up Alpe d’Huez. But on days that his mind and motivation failed him, he would trail in long after the favorites arrived home.

He was also monumentally unlucky. He was almost crippled after hitting a car head-on during Milano-Torino, after it was mistakenly allowed onto the course in 1995. In 1997, he was forced to abandon the Giro when a black cat crossed his path and caused him to crash. 1998 saw him reach the pinnacle of our sport with the Giro-Tour double before 1999 saw him become the first super-star to be singled out for the (suspected) use of EPO during the jet-fueled late Nineties.

Pantani was more than a cyclist for us. 1998 was the year my VMH and I met, and we built our relationship in part as we shared in the excitement as our favorite rider won first the Giro and then the Tour. (Early in our relationship, she hosted a party at her apartment; when I walked in, she had Star Wars, A New Hope playing on the television. Later that night I learned her favorite rider was Pantani. Needless to say, I’ve never looked at another woman since.) The ’98 Tour remains my favorite, with the stage to Les Deux Alpes the high point.

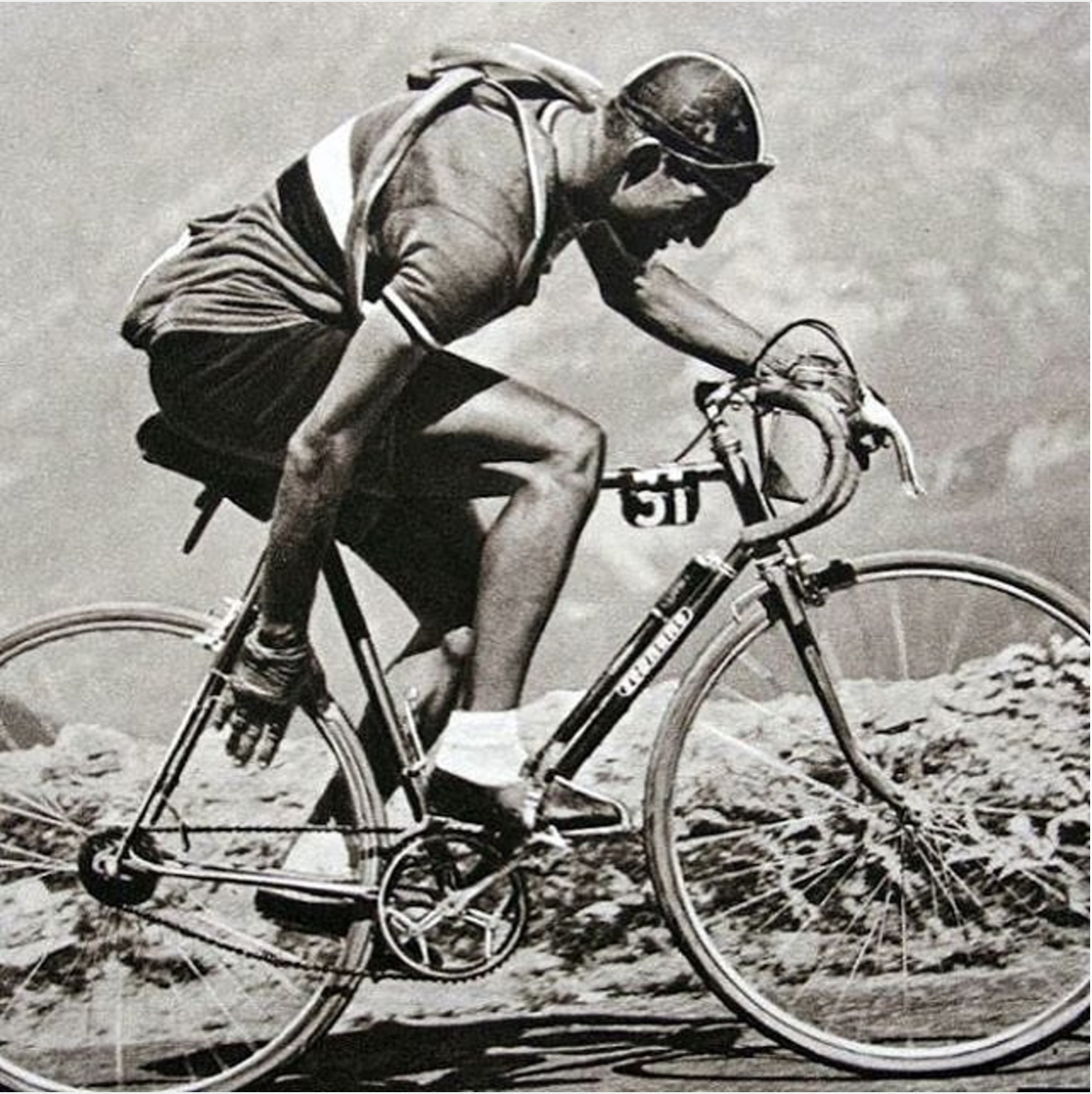

He inspired me – a big, tall, oafish flatlander – to become obsessed with climbing, an obsession I maintain to this day (or, at least I did until January 28). His climbing epitomized the angelic grace of le grimpeur. Climbing in the drops with his face a picture of focus and determination, his climbing could not be described as effortless, but powerful. A sight to behold. Everything about him oozed cool. I modeled my first dream bike after the gloriously beautiful steed he rode in 1998. My VMH, the same weight and height as Marco, modeled her position and climbing style after his.

My heart aches when I think of how this man, who was part of a system which, however full of flaws, he understood. I imagine that he was not a unintelligent nor an ignorant man, but that he was not prepared for the cruelty of the world outside cycling. I can scarcely fathom his sense of confusion and betrayal that the very system and players who taught him Le Metier would so readily cast him aside and leave him on his own. I don’t believe it’s a stretch to compare the scars he received from this experience to those of a victim of abuse. He would never trust his surroundings again.

Several times, he returned to the only world he knew, the professional peloton. But he wasn’t the same. He was bullied, he was teased. Occasionally, he rose above it all to show signs of his former self. Then, he would recede.

2003 was an exciting season as he returned to form and it appeared as though he was finding his own again. Imagine our excitement when, as we planned to visit the Tour for the month of July, rumors broke that he was leaving Mercatone Uno to join another team in order to race the Tour. We were foaming at the mouth at the thought of Ullrich and Pantani shelling Pharmstrong out the back as they partied like it was 1998.

It wasn’t to be. The team transfer didn’t materialize, and Pantani disappeared. The next time we were to hear from him would be the solemn announcement of his death on CyclingNews. I called my VMH and asked if she was sitting down before I told her what happened. It was as if I had given her the news of her brother’s death.

I truly believe he died of a broken heart.