Framebuilding: Subcontractors and Big Names

I’ve made mention before of Rouleur magazine and their amazing, in-depth articles. In one of the past issues, they had a wonderful piece on frame building in the eighties and nineties describing how many of the big names sourced the building of frames – especially custom frames – to subcontractors. The article focused on one contractor in particular, Dario Pegoretti, who went on to start a prestigious boutique bicycle business after the subcontracting business calmed down as advances in technology and frame building processes rendered custom frame building economically impractical for bicycle companies.

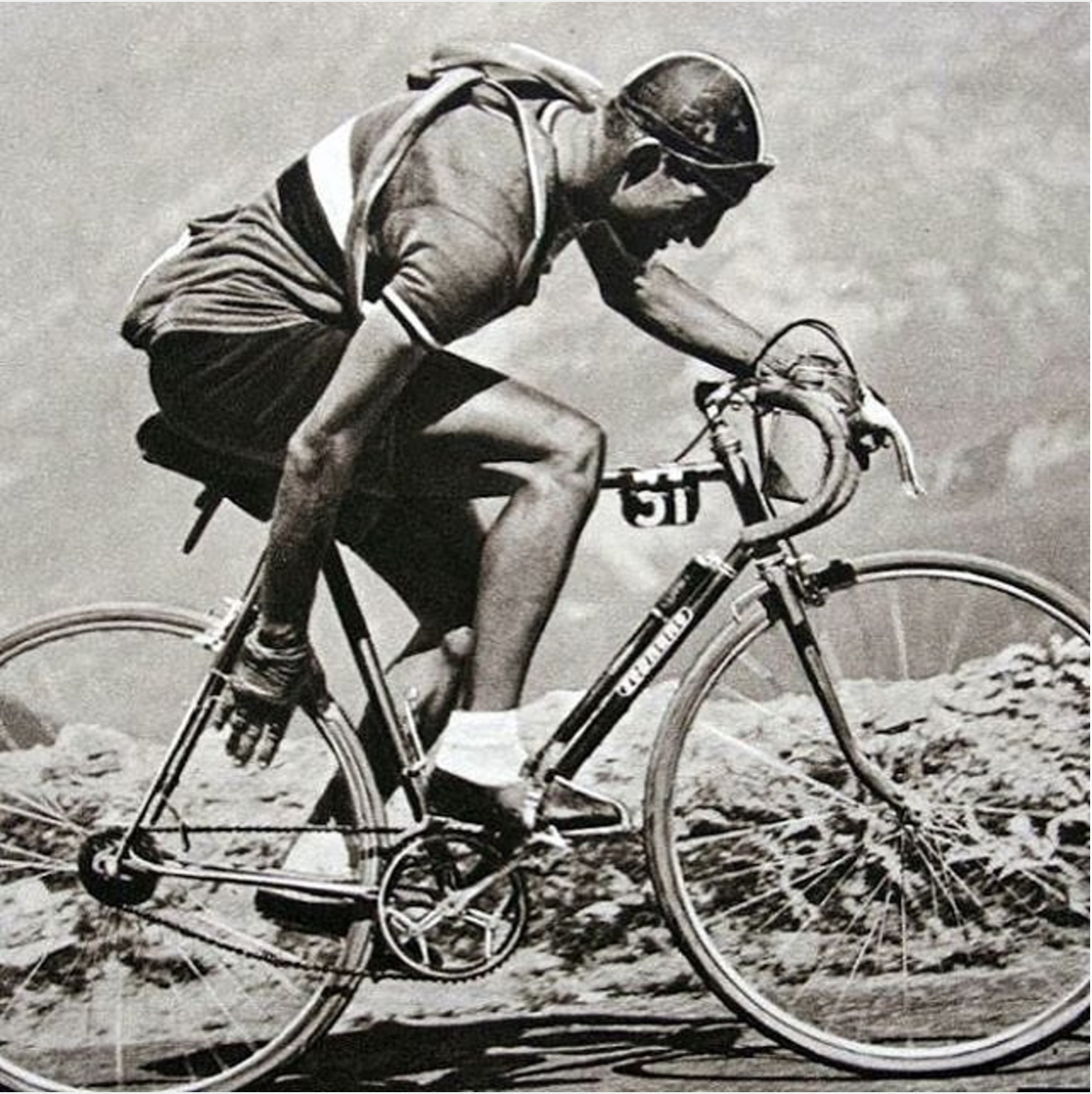

Some of the more observant members of society have possibly noticed that not every person is identical in appearance. In fact, those with the most critical eye for detail have probably reached the conclusion that most people are, in fact, of varying shapes and sizes. This seemingly unimportant fact presents a logistical nightmare for a bicycle manufacturer supplying frames to a professional team, particularly until the late nineties, when nearly every pro bike racer demanded custom geometry or had special material requirements. Custom geometry was in vogue and it resulted in hundreds of one-off, custom frame builds for the manufacturer supplying a team. The solution was to farm this work out to specialists who built the bikes to specification in their personal workshops and sent the frame back to be painted up with the company and team logos. The majority of bikes writing their riders and the company name into the history books were in fact built in tiny workshops by builders like Pegoretti.

I’m guessing a little bit at my next assertion because I wasn’t involved in the decision-making process, but this practice was a logical choice and was easily executed since steel frames were generally built out of fairly limited tube sets and built by using lugs or were TIG-welded together. Unpainted, frames from one company were in most respects indistinguishable from others, pending detailed inspection which might reveal signature details such as a stamp on a lug with the manufacturer’s name or logo. It was a far cry from today’s monocoque or semi-monocoque frame construction featuring proprietary tube shapes and frame design – instantly recognizable even from a distance. Those companies not using carbon or titanium often use proprietary aluminum and steel tubesets which also makes using subcontractors more complicated and they resorted to building their custom frames in-house.

As frame materials progressed towards more exotic and challenging materials such as carbon-fiber and titanium, more and more specialized knowledge was required for construction of the frames. Custom frame building gradually moved away from using an array of subcontractors and towards partnering with a specialized industry leader who had the expertise and equipment to work with the materials. For carbon frame construction, this meant not only the manufacture of tubes, but also bonding the tubes to aluminum lugs in use at the time; TVT was was the preferred partner for this in the eighties and nineties, building frames for everyone from Pinarello to Greg LeMond Bicycles. On the other hand, titanium requires such a high degree of skill and specialized knowledge that the industry leader was in such high demand that they eventually became their own company, Litespeed.

Custom frame building has gradually fallen out of fashion in the pro peleton. Today, while some pros still race custom bikes, most are riding molded carbon frames which are too costly for companies to customize. Riders who once insisted on custom geometry have found that through choices in stem-length, stem rise angles, and seatposts with varying amounts of setback, they are able to tailor the fit of their setup to suit their needs without requiring a custom frame. That said, in some cases, the geometry simply doesn’t work for a star rider and – if the rider is valuable enough – manufacturers have redesigned their frames in order to accommodate them; the most notable case being that of Tornado Tom Boonen and his Specialized Tarmac.

One of my bikes is a steel Bianchi built of Columbus TSX tubing, designed especially for riders exhibiting a condition cyclists commonly referre to as “being fat”. TSX was designed to be more durable and stiff for taller and heavier riders, complete with ovalization of the seat tube at the bottom bracket for added torsional stiffness. I bought the frame from a guy whose credibility I can’t verify but claims he got it from a pro who raced in Europe during the mid nineties and had the frame custom built for him.

There seems to be some degree of likelihood to the claim. The geometry of my TSX from 1996ish and my XLEV2 from 2002 is noticeably different, as you can see from the photos below (aside from the compact geometry). While I’m not saying Bianchi didn’t change their geometry, I like to dream that the TSX was built with love and care in a small workshop by an Italian specialist like Pegoretti – or even Pegoretti himself.

It doesn’t hurt to dream.

[album: http://filemanager.dutchmonkey.com/photoalbums.php?byfile=yes&file=02_Bee.jpg&currdir=/frank.dutchmonkey.com/personal/Pictures/Bikes/|height=500]